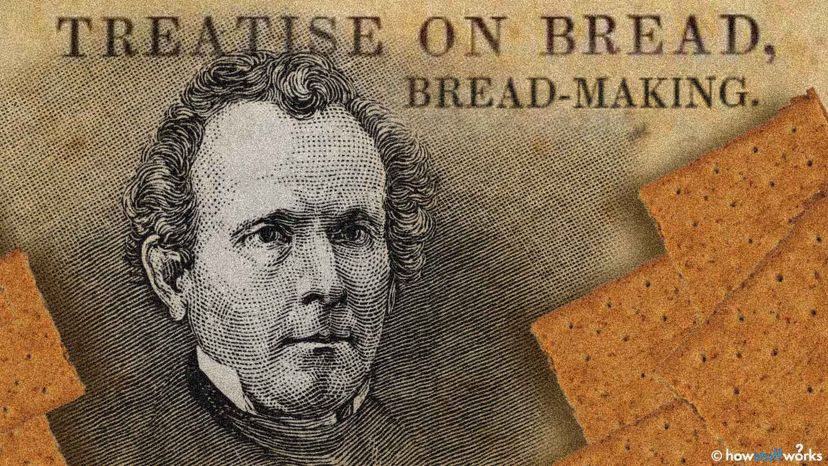

“We can thank American food reformer and religious teacher Sylvester Graham for graham crackers. Though the graham crackers we know today are nothing like the ones he first invented. Library of Congress/HowStuffWorks

“We can thank American food reformer and religious teacher Sylvester Graham for graham crackers. Though the graham crackers we know today are nothing like the ones he first invented. Library of Congress/HowStuffWorks

Let’s face it: One of the best things about making a campfire is making s’mores — the quintessentially American treat consisting of a toasted, gooey marshmallow and a square of melted chocolate pressed between two crisp graham crackers. But have you ever wondered where graham crackers came from or where they got their name?

It turns out the graham cracker was a health food developed in the 1830s from the teachings of an American food reformer and religious teacher named Sylvester Graham who, by all accounts, would be appalled by what passes for a graham cracker today.

"The closest remnant [to the original graham cracker] that exists today is probably the pilot cracker or hardtack," says New York-based food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson. "That was the type of cracker that was commercially produced and available at the grocer or general store."

In other words, the original graham cracker bore little resemblance to the one we enjoy today that’s typically made with refined flour, high fructose corn syrup and a dab of honey for marketing purposes. Instead, Graham’s original cracker called for ingredients including "graham flour," a form of whole wheat flour made by grinding the endosperm of winter wheat into a fine powder and mixing it with the bran and grain. It has a coarse texture, nutty flavor and is not gluten-free.

"It’s funny that of all the things that he talks about with his health reform, that’s the one thing that gets widely adopted and has his name," Johnson says. "[Graham flour] gets adopted by people who may not even be aware of him even toward the end of the 19th century and persists into some of the 20th century. You hear about graham gems and graham bread in cookbooks up to the 1940s and 1950s."

Who Was Sylvester Graham?

Graham was horrified by overprocessing and enriching wheat flour, and believed the loss of fiber and other nutrients in white flour ruined consumer’s health. In 1837, Graham published a pamphlet entitled, "A Treatise on Bread and Breadmaking," and was hailed by the philosopher-poet Ralph Waldo Emerson as "the prophet of bran bread."

Graham was an early proponent and follower of vegetarianism, founding the American Vegetarian Society in 1850. Graham also believed in limiting exposure to most spices, refined sugar and all processed foods. A Presbyterian minister, Graham was a member of the temperance movement, abstaining not only from alcohol but even from using yeast in baking.

"I think that’s why graham crackers became a ‘thing,’ because they were unleavened, they didn’t have brewer’s yeast in them," Johnson says. "The temperance movement was a big part of a certain kind of Protestantism, but the really hardcore temperance people, like Graham, believed you couldn’t use yeast because yeast produces alcohol."

In addition to writing about food, Graham also gave lectures on diet reform that are difficult to separate from his religious philosophy. He had thousands of followers, referred to as Grahamites. He greatly influenced other health reformers who were also religious teachers of the day including Ellen White, an adherent of Seventh Day Adventism and Dr. John Kellogg, another Seventh Day Adventist who, along with his brother, Will, invented cornflakes and founded Kellogg’s.

“Graham flour is made by grinding the endosperm of winter wheat into a fine powder and mixing it with the bran and grain. It has a coarse texture, nutty flavor and is not gluten-free. S. M. Beagle/Shutterstock

“Graham flour is made by grinding the endosperm of winter wheat into a fine powder and mixing it with the bran and grain. It has a coarse texture, nutty flavor and is not gluten-free. S. M. Beagle/Shutterstock

Graham’s Health Food and Religious Views

Graham’s views on diet were linked, not only to physical, but also to moral and spiritual health. He promoted daily bathing, toothbrushing and eating three regular meals per day, but he also believed sex was only useful for procreation. He also thought enjoying food was a sin. Johnson says many of Graham’s recommendations for healthy living — cold baths, sleeping on hard mattresses, and abstaining from alcohol, meat, sugar, refined foods — were similar to the those practiced by self-flagellating monks of the medieval period, which came out of the Plague.

"Many of Graham’s health reforms that happened in the 19th century come out of a series of cholera and typhoid epidemics," Johnson says. "That’s where the water cure comes in, and the emphasis on the health and sanitation of avoiding the excesses of life that people thought might be a factor in disease."

Johnson says prosperity, technological change and new urbanism brought about changes in society not everyone viewed positively. Graham was rightly concerned about food purity and the dangers in commercial food production as populations shifted from farms to cities, but his religious convictions tempered the lasting influence of the man who was a forerunner of the American health food movement.

"He believed there’s less peer pressure to behave correctly if you move to the city where you’re not known to everyone," Johnson says. "A lot of his ideas are about control and how you create order in a time of change and chaos. He stripped a lot of the joy out of life, eating, sex, sleeping and baths. Which is why his actual teachings are not adopted.

"Part of it is the temperance, part of it is the self-denial. Who wants to sleep on a board if you don’t have to? Who wants to take a cold bath if you don’t have to? But graham flour, especially if you’re using freshly ground whole wheat, is delicious. It’s really good and does have a lot more flavor than white flour. I can see why that would be the thing that persists."

Graham died in 1851 at age 57 of complications of receiving opium enemas on doctor’s orders. There are reports that he attempted to reverse anemia by consuming liquor and meat near the end of his life, on his doctor’s advice, thus breaking his own dietary ethics.

Now That’s Interesting

American novelist Louisa May Alcott felt the influence of Sylvester Graham. The Alcotts and other families founded a vegetarian colony known as Fruitlands where they attempted to live off the land. But Fruitlands failed. Louisa wrote that "the world was not ready for utopia yet." The family moved to Brook Farm and kept a "Graham Table" where meat, tobacco and coffee were banned.